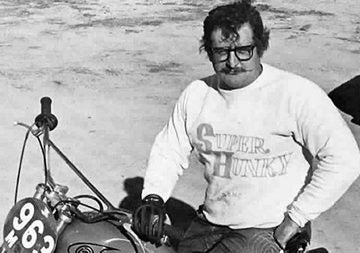

(Hi, folks. Rick Sieman here. This story actually happened, and it graphically points out how sweet revenge can be. Oh, by the way, the name of the club that put all those terrifying hill nightmares in their courses was SoCal. That club is responsible, no doubt, for the gray hairs that I have this very day.)

(Hi, folks. Rick Sieman here. This story actually happened, and it graphically points out how sweet revenge can be. Oh, by the way, the name of the club that put all those terrifying hill nightmares in their courses was SoCal. That club is responsible, no doubt, for the gray hairs that I have this very day.)

There’s this club in Southern California (they’ll remain nameless) that delights in making big hills a part of their events. When you’re on the top of one of their killer hills, you can barely see the bottom. Which is a good thing. Because if you could see the bottom, your socks would probably roll up and down like a broken window shade.

What I’m trying to say is that these hills are flat scary. Descending them is much like playing Russian Roulette with a bow and arrow. You can tell right away if you’re in trouble or not. But at least when you start down one of these nightmare hills, you know that you’ll reach the bottom in one fashion or another. Gravity will do its part and, with or without your assistance, the bike will eventually find its way down the hill.

Which brings us to the hard part—getting up the front part of the hill, so you can get down the back side of the hill. Some of the climbs are nearly impossible (for years I’ve been convinced that they lay out much of the course from a helicopter). To even consider making it up these hills, the rider must get one helluva run at it and keep the machine moving. Miss one gear, or bobble just a hair, and the hike loses forward motion and the rear wheel digs a trench.

This leaves you one of several options. The first and most obvious thought is to descend the hill and take another run at it. More often than not, getting back down one of these hills is like trying to beat a rattlesnake to death with a Twinkie. It can be done, but chances are you’re going to get hurt in the process.

Why?

Simple. There are usual¬ly several hundred big-eyed, panic inspired riders just like yourself, trying to come up that hill. Most of the attempts are of the banzai nature; that is, hold the throttle wide open, close your eyes and don’t shut off until you hear the sound of rending metal or flesh.

Now just picture trying to go down that kind of hill. This then leaves you the option of attempting to get up the remainder of the hill under your own power (most un¬likely), or recruiting the aid of some¬one else.

Naturally, no one is going to stop and help you in the midst of a successful climb, so you just sit there a moment and wait for someone to get stuck in your general vicinity.

Which brings me to this one Sun¬day, several years back. I was stuck on the side of one of these killer hills, with the rear wheel of my gold-tanked Yamaha buried well past the axle centerline. Several attempts to spin my way out proved unsuccessful and the delicate odor of burning clutch plates reached my nostrils.

Hmmm. Time to look around for a little help from a friend.

Just at that moment, I saw a flash of gold (what? another Yamaha identical to mine?) lurch to a stop no less than a yard away. He fired up the stalled engine and proceeded to chum a rooster tail, bury the rear wheel and fry away at his clutch, all to no avail.

I smiled inwardly. Finally the other rider stopped his pathetic efforts and looked around hopefully.

I waved and said, “Whattaya say we help each other up, fellow Yammie rider?”

He nodded in agreement and suggested that we get his up the hill first, because it seemed to be the most natural line. Why not, I thought innocently?

We tugged and sweated and finally extracted the bike from its knob¬by-dug grave. Sweat poured from my forehead, coursed down my cheeks and trickled off the ends of my moustache. I felt like spinning around in a circle and imitating a lawn sprinkler, just for a cheap laugh, but didn’t have the energy to spare.

He fired the Yamaha up, snicked it into low gear and fed the clutch out, while I pushed with all my en¬ergy up the silty slope.

Finally, af¬ter what seemed like an eternity, we made it to the top. I sat down on a rock to catch my breath and mopped the stinging salt out of my eyes with the collar of my T-shirt.

“Okie-doakie, now let’s go get my …” I started to say, only to be interrupted by the sound of the guy I had just helped, bump-starting his bike down the hill.

“Hey, wait just a damn minute, you dirty son of a …” But it was too late. He was gone. And left me standing there with my finger in my nose.

I made a mental note of the happenings, vowing to perform an evil deed on that person if I ever ran into him again. Several evil deeds, in fact. Yep, my mind worked over¬time as I singlehandedly groped up the hill, Yamaha in tow. Mumble, mumble.

Six months later, long after I had forgotten about this incident, I was in another Hare and Hound, sponsored by the same club. This time on another bike, a very tired Greeves. Knowing the reputation of the club for steep hills, I made every effort to not get stuck on the side of one of these cliffs.

But, about 20 miles out, a monster of a hill sapped all of the power out of the engine and brought me to a halt close to the crest. Perhaps 20 yards. As I was sitting there cursing my ill luck, who should come to a trench-digging halt right next to me but, you guessed it—that same dork on the gold-tank Yamaha. It seemed like an instant replay of last time. He dug in so deep that the engine finally stalled, then looked around plaintively for assistance.

At first, I thought about throwing a rock or two at him, but dismissed the idea as being both crude and unsportsmanlike.

Instead, I put on a big smile and waved, “Need any help, friend?”

“Sure,” he replied, “you help me, then I’ll help you. Okay?”

“Sounds only fair enough,” I answered, restraining a giggle, “Looks like you have the best line anyway.”

Five minutes of hard work later, we were at the crest of the hill, looking down at a truly frightening descent. The kind that would give a ski jumper vertigo. He glanced around furtively, obviously looking for the opportunity to split. We were both holding onto the Yamaha’s bars, breathing hard. I snapped around to one side and exclaimed excitedly, “Say, isn’t that a mountain lion over behind that rock?”

He spun around and placed his hand over his brow to keep the sun out of his eyes. This left one person holding the Yamaha. A moment later, no persons were left holding the Yamaha.

The bike, ah…slipped out of my hands.

At first it didn’t move too fast. But then as it crested a 40-foot rock, it started to move. By the time it was 100 yards down the hill, I would say the Yamaha was moving at the equivalent of fifth gear on a level surface—and picking up speed at every second. Quietest bike I ever heard.

He placed both hands over his eyes and shuddered visibly as his gold-tanked Yamaha suddenly be¬came a no-tanked Yamaha.

This seemed like a good time to leave. By the time I got back to my bike, the hill had cleared up enough to enable me to ride back down and take another run at the slope. This time, I had no problem making it to the crest. At the crest was the Yamaha rider, making an obscene gesture at me with the center finger of a gloved hand.

Now, is that any way to act toward someone who has just helped a rider on both sides of a hill?

Your Privacy Choices

Your Privacy Choices