Author Matt Cuddy continues his tale of the rise and demise of the classic Greeves motorcycle brand.

Story By Matt Cuddy

In our first part of our look at the Greeves marque, we explored its beginnings, what inspired Bert Greeves and how a motorized wheelchair manufacturer became a force to be reckoned with in the world of competition motocross and off-road racing. Here’s a video from the early sixties that shows Dave Bickers on a Greeves 360 Challenger, beating factory BSA rider Jeff Smith and his super-trick Gold Star, The end is riveting.

But much like a supernova, Greeves burned brightest before it collapsed in on itself. Back in the late 1960s, when you were going to a race, stuck in that long procession of pick-up trucks with dirt bikes tied down in the back, if you spotted a truck with Greeves in the back, you knew that rider was a serious threat. Just one look at that giant finned cylinder, with the two head pipes curving over the top was like something out of science fiction. All of us who were stuck on stock Yamaha DT1’s, BSA Victors, and A-10 Super Rockets could just stare as the truck went by and hope someday we could afford such a machine.

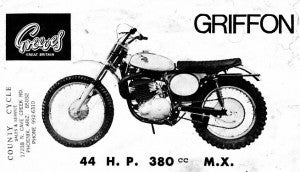

But, in truth, the sun was already setting on Greeves by that time. After two years of success with its Challenger models, the company revamped its motocross line for 1969 with the introduction of the Griffon 250, and Griffon 360/380. Gone was the innovative aluminum down beam frame that had set Greeves chassis apart from its competition, now replaced with a much more conventional-looking frame that was manufactured from Reynolds 531 chrome-moly tubing. Also gone from the regular production Griffon models was Greeves’ unique leading-link front fork, replaced by Ceriani telescopic forks with 7 inches of travel, although you could still special order a Griffon with the leading link fork. Far less conventional in the rapidly changing technology of the era was the fact that the Greeves two-stroke powerplant still featured a non-unitized transmission, which, in and of itself was not a death knell for the brand, but was a sign that Greeves engine technology was lagging behind its competition.

Still, because of manufacturing changes such as light conical brakes, and with engine development assistance from two-stroke expert Dr. Gordon Blair of the Queens University Belfast in Ireland (much of Blair’s engine design wizardry wouldn’t see fruition until 1973l) the Greeves Griffon 380 weighed 20 pounds less than a CZ400, was still very fast and still handled extremely well, helping the brand to remain competitive despite its outdated engines. Greeves was able to keep pace with its European competition from Husqvarna, CZ and Bultaco into the early 1970s. But there were also rumblings from the Far East, as Japanese manufacturer Suzuki had hired Joel Robert to ride its “other-worldly” RH250 works motocrosser. Liberal use of exotic, lightweight materials cut the RH’s weight to a feather 187 lbs, 35 lbs. less than its competition! The burly Belgian was practically unstoppable on the factory Suzukis, reeling off three straight FIM 250cc World Motocross Championships for the brand from 1971-1973.

1971-1975 Greeves Griffon 250cc

Unfortunately for Greeves, its new model 250 Griffon in 1971 had a lot of competition. The Husqvarna 250CR, Bultaco Pursang, Yamaha DT1MX and models from just about every other manufacturer of the time offered customers a wide choice of decent-handling and powerful 250cc dirt bikes. Meanwhile, Greeves was beginning to suffer from the archaic technology of its pre-unit engine/gearbox assembly. Replacing the Amal Monoblock with an Amal Concentric carb didn’t do much to help its success at the race track, and the 250 began to be viewed as more of a sedate off road bike that was at home in the desert or on trails than the motocross track. Since 1971 saw the emergence of quite a few faster and lighter and equally reliable dirt bikes, the Griffon 250 didn’t set the world on fire in sales.

And old Bert Greeves didn’t give a Greeves dealer that big of reason to sell their machines, since he only gave the dealer $100 off the retail price, and that was for a crated, un-assembled bike. Once you put it together, filled up the forks, transmission, greased the steering head bearings, the swing arm pivot, and routed and connected all the cables and electrical system, a c-note wasn’t that much to write home about. That’s why most small off-road motorcycle dealers who sold a Greeves, bumped the standard retail price from $1100 eleven hundred bucks to around $1600 just to make any money. Pricing was another nail in the Greeves coffin.

By this time, Greeves was manufacturing its own top ends, and by 1964 it was using lower ends manufactured by the Alpha Company, since Villiers crankcases were failing with the increased horsepower that Villiers-made top ends were producing. The Griffon was still pre-unit, but the transmission was bolted solidly to the crankcase, making it a semi-unit motorcycle. With proper jetting, a Spanish carb slide, and other Greeves set-up tricks, the Griffons were fast, but so were everybody else’s 250s, many of them straight out of the crate.

Fortunately, for the European brands, Suzuki’s production-grade attempts at the sport had been lackluster, as had Yamaha’s. The latter’s DT-1 enduro model was a milestone in Japanese two-stroke motorcycle development, but was never intended to be a motocross racer. Even so, the DT-1’s inexpensive price and reasonable performance attracted a scad of motocross fans who stripped it of its lights and then modified the heck out of it in an effort to make it competitive with the European machines. Yamaha finally relented and offered DT and RT MX models for sale, but these were still a far cry from the purpose-built production motocrossers being sold from the established European manufacturers.

But then, in 1973, a Japanese brand showed up to the party and profoundly changed the motocross landscape forever. If the sport had been a setting for a science fiction movie, this new brand in the market would have most definitely played the part of the invaders from another planet in the dirtbike universe, bent on destroying about every dirtbike factory in Europe with its own death-ray, code-named “Elsinore.”

Constantly building strength since it first began importing machines to America in 1960, Japanese motorcycle manufacturer Honda shocked the world with its CR250M, which bore the model name Elsinore in homage to the famous Southern California dirtbike Grand Prix that was held in the town of Lake Elsinore. The new machine was Honda’s production two-stroke dirtbike, and it was designed to dominate the competition in the sport of motocross. It was extremely powerful and amazingly light, with its chrome-moly frame, aluminum bodywork and plastic fenders contributed to its 213-lb. dry weight. It was also more affordable than its western competition. The Elsinore flat knocked its European competition back on their heels. It was instantly successful in America, with Gary Jones riding it to victory in the 1973 AMA 250cc Motocross Championship.

Worse yet for Greeves and the rest of the Euros, the Elsinore was really only the tip of the spear that would plant the Japanese flag dominantly in the sport. Yamaha and Suzuki’s initially spindly motocross model designs would rapidly gave way to light, fast and innovative models with names such as YZ and RM. Even smaller Japanese motorcycle Kawasaki jumped into the act with its own line of motocross bikes. Husqvarna, Suzuki and Bultaco ultimately responded with even better machines that, while not as inexpensive, could more than keep pace with their new Japanese rivals. Greeves? Not so much…

But Greeves still built great-looking bikes. They possessed the aura of an older design yet were still darn fast. Most riders who quit riding BSA and Triumph 650cc twins in the desert bought a Greeves, if for nothing else than because of their familiarity with the quirky way in which the Brits built motorcycles. The Greeves still shifting on the right (“wrong”) side, they sported good-quality Ceriani, Metal Profile or Teleco front forks, they made good power down low, and they would top out at around 70 mph for the 250, and 80 mph for the 380. Also, amazingly enough, a Greeves didn’t suffer from constant electrical demons, or major break downs like their BSA or Triumph cousins did. They had a solid reputation as damned reliable bikes—a Herculean feat considering they sported Lucas electrics and an English Amal carburetor!

1973 Greeves Griffon 380 Q.U.B.

While it was drowning in the sea of newer, faster and lighter motocross bikes from Europe and Japan, there was still hope for Greeves in the open class where there were far fewer competitors to deal with at the time. In order to keep up with the Japanese onslaught, in 1971 Bert went to Dr. Gordon Blair, at the Queens University of Belfast, a two-stroke expert, to get the big bore Greeves 380 to produce more power. Blair got the horsepower up from 33 to 44 in 1971, but the designs weren’t incorporated until 1973 model, which became known as the Griffon 380 Q.U.B. in deference to Queens University Belfast.

The Q.U.B. was the product of a collaberation between Greeves and Queens University Belfast’s Dr. Gordon Blair, a two-stroke engine expert. Blair was able to up the power level from 33 to 44 horsepower, but Greeves customers still had to contend with the model’s slow-handing chassis and quirky pre-unit engine/transmission configuration. The Q.U.B. also shifted on the right side at a time when most contemporary motocross models featured the shifter on the left side. [/caption]The Q.U.B. was fast, maybe the best Greeves motocrosser of all time, but the delay in implementing Blair’s engine specs had given its Japanese and European rivals even more time to evolve their machines. I once spoke with Jim Connolloy, a Greeves rider who won the Scrambles Championship from 1971 to 1973 on a Greeves, and he told me that the QUB 380 was as fast as any Bultaco, AJS, Yamaha or about any other open-class two-stroke of the time. Being 20 lbs. pounds lighter than most open bikes didn’t hurt, either; the Q.U.B. weighed just 220 lbs wet.

Take a look at this sales brochure photo for the Q.U.B. 380, and check out the fork rake. It’s really more like a chopped Sportster than a dirtbike, and it’s easy to see why Greeves made such great-handling desert bikes and only mediocre-handling motocross machines. The bikes liked going straight and were very forgiving motorcycles in desert situations that called for a lot of stability. One rider I know once quipped that when he got “out of shape” on his Greeves in a rough section of desert, cranking on the throttle usually straightened things out for him.

Take a look at this sales brochure photo for the Q.U.B. 380, and check out the fork rake. It’s really more like a chopped Sportster than a dirtbike, and it’s easy to see why Greeves made such great-handling desert bikes and only mediocre-handling motocross machines. The bikes liked going straight and were very forgiving motorcycles in desert situations that called for a lot of stability. One rider I know once quipped that when he got “out of shape” on his Greeves in a rough section of desert, cranking on the throttle usually straightened things out for him.

In The End…

When I was racing a modified 1969 AT1MX Yamaha in the Desert Racing Association back in 1974, I was in the Trailbike “C” class. My AT1 sported a cut stretched and lowered frame, a 175 barrel and head, was ported by EC Birt, and had a fork kit and Curnutt shocks out back. One time at California City, I was stuck in one of the infamous endless sandy whoops with which the Checkers seemed to enjoy torturing their racers. The dust was so bad I had about 5 feet of visibility, and was pounding through the whoops in fourth gear. In front of me was a Greeves Griffon 380 with some squid riding it, and I tried for at least 5 miles to pass him, only to be kept back by the tank-slapping Greeves. Finally a little trail opened up next to the whoops, and I was able to blow by the Greeves like a top fuel dragster against a Nash Rambler. Then the Checkers routed us up into a mountain single track that had giant boulders and slippery rocks covering the trail’s surface.

Somehow, the Greeves rider had got in front of me again, and there I was, stuck behind this big red motorcycle, trying to dodge the rocks that kept spitting off it’s 4.00 x 18 Dunlop. Ah, but I was on a motorcycle that had decent brakes, and soon a bottleneck formed around the infamous “So Cal Downhill,” which went straight down between giant boulders and was made up of loose shale. Luckily for me, my AT1 sported a giant skid plate that I used with great effect by slamming it into a giant rock to slow down, stop, and try to plot a safe course down this miserable hill.

I was stopped on a boulder, teetering back and forth, when the guy on the 380 Greeves went screaming by me, its rider was screaming for mercy from the motorcycle gods. His foot had the rear brake pedal slammed so hard, it was almost touching the ground. When I finally made it to the bottom, I didn’t see the Greeves again, and after another 20 twenty or so miles of hellish whoops, danger tape and abandoned Hudsons, right next to a railroad track, the race ended and I got my finisher pin.

Exhausted and dehydrated to the point of passing out, on my way back through the pits I spotted a Greeves being loaded onto a three-rail trailer. It looked awe-inspiring, the giant fins and dual head pipes making the motor appear as it displaced at least 1000cc. But, judging by all the goo, mung and drool covering the bike, it signaled to me at my young age that even though the Greeves looked the part, some kid on a hopped up 125cc Yamaha could give it a hard time, and beat it.

While Greeves produced stellar off-road motorcycles that won many races in the beginning of the company’s lifespan, the lack of deep pockets prevented it from redesigning and releasing modern suspension designs, modern engines and frame geometry, and that ultimately doomed the marque. By the end of the 1970’s, Greeves, DOT, Cotton, AJS and BSA had all shuttered their factory doors, and Triumph was barely hanging on by a thread. Of the casualties, Greeves was one of the last to close, offering the Griffon 250 and Griffon 380 until 1977.

It was a sad end to a fine motorcycle, but the Greeves brand still holds a place in the hearts of many old-timers and vintage enthusiasts to this day. Greeves are the odd ducks at any given vintage off-road or motocross event, but those ducks can still fly, and Greeves trials models continue to be a favored brand in vintage competition.

Long live Greeves!

Your Privacy Choices

Your Privacy Choices